National Missing in Action and Prisoners of War (POW/MIA) Recognition Day is observed on the third Friday of September each year in the United States. It was established by Congress in 1998 in order to honor those who were prisoners of war and those who are still missing in action. The black and white flag symbolizing POW/MIAs is well known as a solemn reminder of our obligation to always remember the sacrifices made to defend our Nation. Nonetheless, its history is a fairly short one.

In 1970, Mary Hoff, a member of the National League of Families, recognized the need for a symbol of America’s Missing in Action and Prisoners of War (POW/MIA). Her husband, Navy pilot Lt. Cmdr. Michael Hoff, had been missing since January 7, 1970. Mrs. Hoff contacted Norman Rivkees, Vice President of Annin & Company, which manufactured all flags for the United Nations member states. Rivkees and an advertising agency employee, Newt Heisley, designed a flag to represent the missing. Heisley was a former WWII pilot and graphic designer for a New Jersey advertising agency in 1971 when he sketched the future design of the POW/MIA flag.

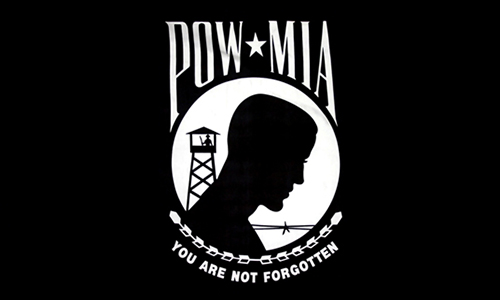

The flag is black, and features a white disk bearing in black silhouette the bust of a man, watch tower with a guard, and a strand of barbed wire; above the disk are the white letters POW and MIA on each side of a white 5-pointed star; below the disk is a black and white wreath with the motto: “You are not Forgotten.”

The model for the captured soldier was his son Jeffrey, then 24, who had just returned from U.S. Marine training gaunt and sick with hepatitis. The words that Heisley stretched across the bottom of the flag — “You Are Not Forgotten” — were inspired by memories of piloting transport planes on long flights across the South Pacific during World War II.

While flying, he thought about “being taken prisoner and being . . . forgotten…that experience came back to me, and I wrote down the phrase ‘You are not forgotten.’ ”

Following National League of Families approval, the flags were manufactured for distribution. Wanting the widest possible dissemination and use of the symbol, it was not trademarked or copyrighted. The widespread use of the POW/MIA flag is not restricted legally, nor do profits from its commercial sale benefit the League.

Heisley once said in an interview, “It was intended for a small group. . . . No one realized it was going to get national attention.”

On March 9, 1989, a POW/MIA flag that had flown over the White House on the 1988 National POW/MIA Recognition Day was installed in the U.S. Capitol rotunda as a result of legislation passed by the 100th Congress. The National League of Families’ POW-MIA flag is the only flag ever displayed in the rotunda, and the only one other than the Flag of the United States to have flown over the White House.

On August 10, 1990, Congress passed U.S. Public Law 101-355, which recognized the POW/MIA flag and designated it “as the symbol of our Nation’s concern and commitment to resolving as fully as possible the fates of Americans still prisoner, missing and unaccounted for in Southeast Asia, thus ending the uncertainty for their families and the Nation”. However, the design has come to represent all U.S. troops missing in military conflicts.

The importance of the POW/MIA flag lies in its continued visibility as a constant reminder of the plight of America’s POW/MIAs from all wars, including those now ongoing.

The flag’s popularity has expanded more quickly than any other during the last 50 years.

Other than “Old Glory”, the POW/MIA flag is the only flag ever to fly over the White House, having been displayed in this place of honor on National POW/MIA Recognition Day since 1982.

The 1998 Defense Authorization Act required that the POW/MIA flag fly six days each year; Armed Forces Day, Memorial Day, Flag Day, Independence Day, National POW/MIA Recognition Day, and Veterans Day.

The POW/MIA Flag is flown on the grounds or the public lobbies of major military installations, all Federal National Cemeteries, the Korean War Veterans Memorial, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the White House, the United States Post Offices and at the official offices of the Secretaries of State, Defense and Veterans Affairs, and Director of the Selective Service System. Civilians are free to fly the POW/MIA flag whenever they wish.

In the U.S. armed forces, the dining facilities display a single table and chair in a corner draped with the POW/MIA flag as a symbol for the missing, thus reserving a chair in hopes of their return.

The Department of Veterans Affairs voluntarily displays the flag 24/7. The National Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Korean War Veterans Memorial and World War II Memorial are now also required by law to display the POW/MIA flag daily, and most State and local governments have adopted similar laws.

The DoDs Defense Prisoner of War/Missing Personnel Office is responsible for investigating the status of POW/MIA issues. We still have 83,165 personnel unaccounted for including 73,520 from WWII, 7,874 from the Korean War, 126 from the Cold War, 1,639 from the Vietnam War, and 6 from Iraq, Afghanistan and other conflicts.

Newt Heisley was “extremely, extremely proud” of designing the flag, and he was humbled by the attention that came with it. “I didn’t do it for personal gain or acclaim,” he said, “I did it for the men who were prisoners of war or missing in action. They’re the real heroes.”

References

o http://www.latimes.com/local/obituaries/la-me-newt-heisley20-2009may20-story.html

o http://www.pow-miafamilies.org/powmia-bracelets/

o http://www.historynet.com/the-story-of-the-powmia-flag.htm